On 28 February 2024, Computer Sweden wrote that the Swedish Tax Agency had now decided to use Office 365 and Teams.

This sparked many reactions. For example, the Confederation of Swedish Enterprise proclaimed that the Swedish Tax Agency can finally use American cloud services. A director at a large consulting firm – which is a Microsoft Cloud partner – wrote ”Finally! I feel my prayers have been heard. The Swedish Tax Agency’s staff can use working tools.”

The Swedish Tax Agency later published what it called a preliminary assessment and wrote ”At present, there is no decision that the Swedish Tax Agency will purchase Microsoft 365 and Teams.”

A supplier of alternatives to Microsoft 365 and Teams has also commented on the memorandum.

We believe that the Swedish Tax Agency’s report warrants comment for several reasons.

This article was written by Arman Borghem, who worked at the Swedish Tax Agency as a cloud strategist between April 2021 and March 2023.

The comment in brief

The approach described in the report means that no documents, files or emails will be stored in the Microsoft’s cloud. Teams chats will be automatically deleted after 24 hours. No information subject to secrecy under the Swedish Public Access to Information and Secrecy Act (OSL) shall be handled in chats. No sensitive personal data shall be handled in chats. Features such as file sharing, recording, live subtitles, transcription, telephony, etc. shall not be used. AI features are not considered at all. In other words, usage is heavily restricted. Despite this, licences of a more expensive type will be used.

The report’s summary states that ”The working group’s preliminary assessment is that there are no legal, security related or functional obstacles to the Swedish Tax Agency and the Swedish Enforcement Authority using Entra ID, M365Apps or Teams.” (Cleura’s emphasis) This is also what the Swedish Tax Agency writes on its website.

It is difficult to understand how the agency came to this conclusion. That is because the report itself states that:

- The Swedish Tax Agency will not be able to fulfil its responsibility under Section 4 of the Swedish Archives Act if it transitions M365, Teams and Entra ID, (p. 10).

- A risk analysis from an information security and IT security perspective remains to be done (p. 13).

- Functionality shall be limited ”to meet secrecy and personal data processing requirements” (p. 4 of Annex 3).

What has been presented as the central conclusions of the report thus seems to be contradicted by the report itself.

The report has identified at least one legal obstacle to moving to the Microsoft solutions. It seems premature to conclude that there are no security related obstacles when the most essential elements of a security assessment remain to be done. Finally, the Tax Agency has concluded that feature after feature needs to be switched off – what does this mean if not functional obstacles?

US cloud service providers are subject to US surveillance laws, and have stated that they take steps to ensure that they comply with disclosure requirements which are valid under these laws. Such disclosures involve deviating from the controller’s instructions. The GDPR requires processors to take steps to ensure that they only process personal data in accordance with the controller’s instructions, unless they are obliged to do otherwise under EU law or the national law of an EU/EEA member state. These rules are set out in Articles 28(3)(a), 29 and 32(4) GDPR. US surveillance laws are neither EU law nor the national law of an EU/EEA Member State. It therefore appears that US cloud service providers do not take the steps required of them under the GDPR, which suggests they cannot be engaged as processors under Article 28(1) GDPR. The Swedish Tax Agency’s report does not deal with this question.

The Swedish Tax Agency and the Swedish Enforcement Authority investigated Teams already in 2021. The authorities then concluded that they for several reasons could not replace Skype for Business (operated on-premises) with Teams. The report does not appear to give a fair account of the 2021 Teams report.

The report does not seem to have fully safeguarded the agency’s independence as there are signs that the report was partly written by an external party acting in Microsoft’s interests.

The investigation does not analyse the economic risk to the Swedish Tax Agency and the Swedish Enforcement Authority as a result of various forms of lock-in in the Microsoft solutions.

What has the Tax Agency assessed?

The Swedish Tax Agency’s investigation is based on a very limited use case:

- No documents, files or e-mails are stored in Microsoft’s cloud. All such data are managed by the Swedish Tax Agency.

- The use of Teams is severely restricted. The proposal is that all chats are automatically deleted after 24 hours. No information covered by confidentiality will be handled in the chat. No sensitive personal data will be handled in the chat. No files will be shared over Teams.

- Internal Teams meetings will apply Microsoft’s end-to-end encryption. This turns off several features. File sharing, recording, live subtitles, transcription, telephony and other features will not be used.

- External meeting participants will need to install the Teams client software to participate in meetings with end-to-end encryption. Such meetings will not be platform independent as the Teams desktop client is only officially supported on Windows and macOS.

AI functions are not touched upon at all, and it can be assumed that they are not included either.

We can assume that the majority of all organisations using Microsoft 365 and Teams today would have to severely limit their use if they choose to follow the Swedish Tax Agency’s example.

The proposal means that the Swedish Tax Agency would pay for the more expensive type of Microsoft licences, even though a lot of features would not be used. Why these restrictions?

With regard to Teams meetings between agency staff, the working group has chosen to ”only investigate a scope of meetings with limited functionality in order to meet the requirements of confidentiality and processing of personal data.”

The investigation also states that ”It has not been possible within the framework of this basic investigation to sufficiently highlight all relevant aspects of a transition to the products in question. Some questions therefore remain, such as regarding archiving, data protection and IT and information security, which must be dealt with in further work.”

Nevertheless, the investigation states that ”The working group’s preliminary assessment is that there are no legal, security or functional obstacles to the Swedish Tax Agency and the Swedish Enforcement Authority using Entra ID, M365Apps or Teams.”

Against this background, we wonder if the working group has considered its own report’s section on archiving rules applicable to the Swedish public sector. There it is explicitly stated that the Swedish Tax Agency will not be able to exercise its responsibility under the Archives Act if the agency switches to MS365, Teams and Entra ID.

The investigation further states that a risk analysis remains to be done, both from an information and IT security perspective. The investigation contains no information classification and associated risk assessment, either per agency branch or at an overall level. From an information security perspective, the investigation does not, for example, take into account the total amount of data that would be transferred to Microsoft regarding how the Swedish Tax Agency’s staff use the solutions and which external parties the authority has meetings with.

We now continue with some additional questions raised by the investigation.

Usage guidelines can give an illusion of security

The 2024 report assumes a limited use case where staff are not allowed to enter sensitive personal data in the Teams chat. One may wonder how realistic such a restriction is. The 2021 Teams report stated:

”Although internal guidelines can be used to help limit the amount of sensitive and confidential information that is made available to Microsoft, it would not [be] possible to prevent large amounts of sensitive and confidential information from being made available to the company if Teams were used as the main video conferencing and collaboration platform, especially given the authorities’ activities and the number of staff members concerned. Furthermore, excessive restrictions on what may be said or shared when using Teams would undermine its value as an effective collaboration platform.”

This reasoning still seems relevant.

Sensitive personal data (in fact, special categories of personal data) can appear in the workplace in a range of contexts. The proposed rules would therefore appear to lead to, for example, the following restrictions:

- An employee may not write on Teams to their manager or colleagues that they are sick or are staying home to take care of their sick child. The employee may not even indicate this in their Teams status. Employees may not write to their colleagues on Teams to inform them that another colleague is sick or staying home to take care of their sick child.

- An employee on sick leave and their manager cannot use the Teams chat to discuss wellbeing and recovery.

- Caseworkers may not use the Teams chat for discussions where information about a person’s health is revealed. The Swedish Tax Agency handles, for example, health care benefits and tax reductions for travelling to work in the event of illness or disability. A case number in a chat may be sufficient to connect a discussion to a specific person, thus leading to processing of personal data.

- Employees may not write anything on Teams that reveals information about their own health, or the health of a colleague, in relation to work. This could be anything from the need for computer glasses to a wheelchair ramp.

- HR staff and managers may not use the Teams chat for discussions revealing that an employee is a member of a trade union (for example, that an employee wants a trade union representative to attend a meeting about salary), that an individual appears to have a drinking problem, or that an individual has been mistreated because of their ethnicity, religion or sexual orientation. A member of staff who wishes to report any of these issues to their manager or HR is also not allowed to use the Teams chat.

- Trade union and employer representatives may not use the Teams chat to communicate with each other in trade union matters.

The report does not deal with processing of personal data related to criminal offences. Such processing can be at least as sensitive as the processing of special categories of (sensitive) personal data. If the processing of criminal offences data is to be handled similarly, this will mean further restrictions on what staff can discuss in Teams chats. This applies not least to staff in the Swedish Tax Agency’s law enforcement activities, but also to those who handle ”ordinary” cases where suspected crime can be revealed, such as tax fraud, incorrect registration of addresses, or front companies.

In theory, guidelines can of course limit staff behaviour in terms of what information they can handle and where. However, the question is whether the guidelines can in practice be understood, remembered, correctly applied and receive legitimacy among staff. Especially when there are over 10,000 staff members all across the country, with a wide variety of tasks.

If staff are not allowed to chat with each other about the topics exemplified above, at least not freely, the question is what tools they are expected to use instead. If the Swedish Tax Agency is forced to have a parallel chat tool for certain topics, why not go for that tool alone? Why not spare staff the administrative burden of constantly thinking about what they are allowed to write and moving between chat tools to find relevant information? Why expose the agency and individuals to the risk that employees still make mistakes, and burden finances and internal resources with two different tools?

Emergency readiness and role in civil defence

In 2021, the Swedish Tax Agency and the Enforcement Authority concluded that the agencies could not replace Skype with Teams. The investigation describes the 2021 Teams investigation as follows:

The 2021 investigation primarily covered the legal conditions for using Microsoft Teams. In the renewed investigation, other aspects have also been taken into account, such as emergency readiness and resilience, benefits to the organisation, the Swedish Tax Agency’s ability to deliver an IT workplace to other authorities and the fact that the alternatives to Microsoft 365 that are available have proved difficult to realise.

The 2021 inquiry had eight main sections. Three of these focused on legal issues. One section focused on benefits to the organisation, one section focused on the possibilities of using Teams based on a risk assessment and one section focused on appropriateness. Among other things, the section on appropriateness stated:

Already today, large amounts of information from Swedish authorities are collected at these three cloud service providers [Azure, AWS and GCP], which increases society’s vulnerability, as disruptions at any of these cloud service providers will affect many authorities at the same time … Against the background of, among other things, the increased threat to Sweden, the rearmament of [Sweden’s] total defence, the more strict Protective Security Act and developments in the field of data protection, it is obvious that authorities need to consider more parameters than before, primarily regarding security and digital sovereignty. It is therefore not possible for the Tax Agency and the Enforcement Authority to ignore the risks to Sweden’s sovereignty in their choice of solution for digital communication and co-operation.

The new investigation does not mention resilience other than where it is suggested that the 2021 investigation did not consider resilience. We cannot see that the new investigation provides any reasoning on how the Microsoft 365 solutions would affect the Swedish Tax Agency’s resilience, preparedness or resistance capability – either positively or negatively – as part of the civil defence.

The investigation states that the Swedish Tax Agency may need to keep Skype, which the agency currently operates on premises, in parallel with Teams. However, the investigation does not discuss how long Skype is expected to be a viable alternative and what the agency’s plan is in concrete terms for the day Microsoft stops updating Skype.

Scope of the investigation

The investigation has had a limited remit and leaves essential questions unanswered. We highlight some parts here where this is apparent.

A starting point for the investigation is a hypothetical scenario in which the implementation of the products is limited to a minimum level, e.g. with regard to what data is transmitted to Microsoft and what functionality is activated. This has enabled the analysis to focus on the basic version of the products. The results of this initial investigation thus form the basis for future investigations into whether additional functionalities can be added.

It has not been possible within the framework of this basic investigation to adequately examine all relevant aspects of a transition to the products in question. Some questions therefore remain, such as regarding archive management, data protection and IT and information security, which must be dealt with in further work.

The working group’s initial task has been to investigate whether there have been changes that mean that there are currently legal conditions for proceeding with an in-depth assessment of the services in question.

The report is based strictly on the established delimitation. The amount of information created and processed through the Swedish Tax Agency’s use of the services in question has been limited to a necessary level. It remains to be analysed how the services can be used in practice and what technical and administrative challenges are identified … This report needs to be followed by a more in-depth study. Risk analysis from both an information and IT security perspective needs to be carried out.

A problem of a fundamental nature is that service and diagnostic data is preserved according to Microsoft’s default settings. This means that, in practice, the dates for deletion of public sector documents (in scope under Sweden’s fundamental laws and other provisions) will be determined by Microsoft, not by the Swedish Tax Agency. It is unclear whether the Swedish Tax Agency, after having made its own assessment of how long the documents are needed for its operations, can give Microsoft instructions on which deletion deadlines should apply to the documents or that the documents should be preserved. Furthermore, it is Microsoft’s routines, which may change over time, that govern what information is entered into the logs for service and diagnostic data and how the logs work. In these respects, the Swedish Tax Agency will thus lack a real ability to exercise its archival responsibility under Section 4 of the Archives Act, if the Swedish Tax Agency switches to M365Apps, Teams and Entra ID.

The view on disclosures to third countries

The investigation seems to assume that it is possible to make a risk assessment under Article 32 of the GDPR to accept the possibility that third country authorities can access data that the Swedish Tax Agency makes available to Microsoft. It may be assumed that the investigation refers to Article 32(1) of the GDPR.

However, the investigation’s starting point does not seem to be compatible with the GDPR. The rules on using processors state that the processor’s guarantees must relate to measures taken in such a manner that processing will meet the requirements of the GDPR and ensure the protection of the rights of persons. This requires more than simply meeting the security requirements of Article 32(1). For example, the GDPR also includes the data protection principles in Article 5 and the requirement for a legal basis in Article 6.

In addition, the GDPR has specific rules aimed at protecting personal data held by a processor from being disclosed to third country authorities. These rules are found in Article 28(3)(a) and 32(4) GDPR. The Swedish Tax Agency has not considered these rules in its investigation, which is a shortcoming.

Cleura describes these rules and their meaning in the section GDPR protection against access from third countries in the report What your organisation needs to know about the third adequacy decision.

The EDPS, which is the supervisory authority for the EU institutions, has assessed that the European Commission has used Microsoft 365 unlawfully for several reasons. Specifically, the EDPS points out that the European Commission, under rules equivalent to Article 28(3)(a) GDPR, did not ensure that only EU law or the national law of a member state can prevent the processor (Microsoft and its sub-processors) from informing the controller (the European Commission) of disclosures of personal data in the EU to third country authorities. The European Commission had also not done enough under the provision equivalent to Article 32 GDPR to ensure the integrity and confidentiality of personal data.

End-to-end encryption (E2EE)

In the investigation, the Swedish Tax Agency places confidence in the end-to-end encryption (E2EE) that Microsoft offers in Teams for those who pay for a more expensive licence.

We do not believe it is wise to rely on encryption that Microsoft fully controls in order to protect data in Microsoft’s cloud from US authorities. Indeed, the functioning of such encryption appears to rely in practice on contractual guarantees. US intelligence laws can override contractual guarantees.

As we have discussed in our report US vs. European surveillance: analysing differences in the protection of rights when using cloud services, US intelligence collection laws like FISA 702 can compel a US cloud service provider to take all necessary measures to accomplish an ”acquisition” of information.

It may well be the case that Microsoft cannot break the encryption of a data stream once it has been encrypted in the way Microsoft describes how the end-to-end encryption in the Teams service and software is intended to work. However, it is Microsoft which fully controls how the Teams service and software work. The source code is also closed, with no way for a customer such as the Swedish Tax Agency to both review the source code and verify that the software running on the Swedish Tax Agency’s clients, as well as in Microsoft’s cloud, is actually built from the source code that is reviewed.

Therefore the question arises: can Microsoft be compelled to change how the Teams service and software works, at least in certain cases? For example, could Microsoft send an instruction to the Teams software used by a particular organisation – perhaps even by specific individuals – to use encryption keys that Microsoft already has copies of? In that case, it would seem possible for Microsoft to decrypt data streams passing through Microsoft’s cloud.

The Swedish Tax Agency’s investigation seems to assume that Microsoft’s contractual guarantees can be relied upon without exception for what US law can force Microsoft to do. There is no analysis of this in relation to Microsoft’s end-to-end encryption and what ability the Swedish Tax Agency has – if any – to subsequently discover if an encrypted data stream has been decrypted.

We therefore do not see that it has been shown that encryption where Microsoft decides how the keys are handled can provide the Swedish Tax Agency’s data with appropriate protection. If we assume that the encryption is meant to protect against access by US authorities, it also does not seem like the encryption fulfils the encryption for third country transfers that the EDPB describes in recommendations 01/2020.

Against this background, we note that our conclusions on encryption in the report What your organisation needs to know about the third adequacy decision remain relevant.

The investigation’s ability to act independently

Parts of the investigation, in particular parts of sections 2.2.1, 2.3 and 2.4 of the Annex on Teams, appear as if they could have been written by Microsoft or by someone acting on behalf of Microsoft.

We reach this conclusion for the following reasons:

- Some statements about Microsoft’s services are accepted as established truth, rather than being described as information provided by Microsoft.

- Some statements even appear as if they could have been marketing material from Microsoft. For example:

- Det är väsentligt att poängtera att Microsofts insamling, bearbetning och användning av diagnostikdata regleras av deras dataskyddspolicy samt tillämpliga dataskyddsförordningar, såsom Allmänna dataskyddsförordningen (GDPR) inom Europeiska unionen. Microsoft förbinder sig att hantera denna data på ett sätt som respekterar användarnas integritet och säkerhet”. (translated into English, this would be ”It is essential to emphasise that Microsoft’s collection, processing and use of diagnostic data is governed by its privacy policy and applicable data protection regulations, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) within the European Union. Microsoft is committed to handling this data in a way that respects the privacy and security of its users.”)

- The language in these sections is in part unnatural or incorrect (”data protection regulations”) in a way that suggests direct translation from English.

Lock-in, increased costs and loss of control

The 2021 Teams study considered the risks of vendor lock-in and price increases for Microsoft’s cloud services. The new report does not.

What the report mentions is that the agency needs to have an exit strategy, investigate possible alternative solutions and have alternative ways of communication in cases where Microsoft’s services are unavailable. So far so good. However, the report does not explain for what data there must be an ability to migrate to a different supplier, with how little notice this must be possible and how this would be accomplished. A different supplier’s solution must first be introduced in order to be used as an alternative communication route, or in order to continue using exported data.

When an organization makes itself dependent on a specific supplier’s solutions, without having a real alternative, the supplier is put in a position of power. The more important the supplier’s solution is for the organization, and the more difficult it is for the organization to change supplier, the stronger the supplier’s position becomes.

This applies both to the supplier’s pricing power and the supplier’s freedom to unilaterally change the services and the contract terms that govern how the services are delivered. Here we will primarily focus on the economic consequences.

The case of vendor lock-in in Denmark

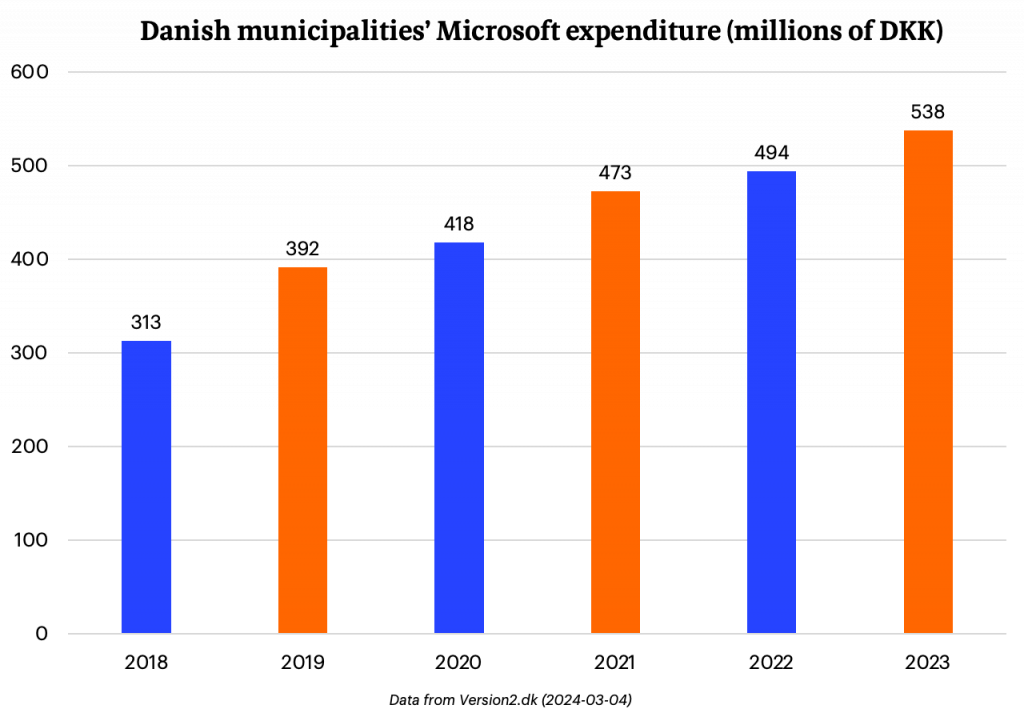

In Denmark, the public sector is deeply dependent on Microsoft. We also have a good picture of the economic consequences of this. Danish media, not least the publication Version2, but also Danish public service media, have devoted considerable attention to the issue.

The vendor lock-in is “fundamentally problematic”

In 2018, Danish municipalities paid at least DKK 313 million to Microsoft; by 2023, the figure is around DKK 538 million. An increase by more than 70 percent.

In Denmark, there is no doubt that this is a problem. The issue has been raised at the government level. Denmark’s liberal Minister for Digitalization has commented on the dependency to Version 2, describing it as “fundamentally problematic”, adding “When technology giants use their dominant position to raise prices without us being able to opt out [of using their services], we have to spend even more tax money without getting more value.” Microsoft itself sees no issue with the pricing, which it has described as “fair”.

The Danish government has now set aside money to investigate promoting the use of open source in the public sector. The government has also set up an expert group because of the tech giants. Version2 reports that the chairman of the expert group shares the concerns of the Minister for Digitalization. He sees the dependency as a major societal concern. “You give up the possibility of democratic control that we have in other areas. It just doesn’t exist in the same way in this area. It is as if we have forgotten that digital is also a form of infrastructure that is actually very critical for a society, and that is important to both invest in and have some kind of control over,” he says.

The chair of the Association of Municipal IT and Digitalization Managers in Denmark, who is himself head of IT at a municipality, has also highlighted the vendor lock-in concerns from a municipal perspective. While Microsoft’s products do improve over time, he tells DR that “The extra things we get we can’t necessarily use to provide services to citizens more efficiently. That makes it unlikely that we can find savings elsewhere.”

As license costs increase, big IT providers rake in money

In Swedish media, Computer Sweden has cited a report stating that public sector spending on IT services has increased by 25 percent since 2019. “And it’s the big IT service providers that are raking in the money. Although 98 percent of the suppliers that sold to the public sector between 2019 and 2022 were small and medium-sized enterprises, the large companies, which accounted for only two percent, accounted for 67 percent of public sector payments for IT services.”

It is sometimes argued that US cloud service providers are necessary to meet the welfare challenge, where fewer people have to support a population growing older. In October 2023, Version2 reported:

The public sector is experiencing large price increases for IT licenses, so large that the Capital Region of Denmark laid off 150 employees in the spring. If you look at one of the largest IT suppliers to municipalities, Microsoft has generally increased the price of licenses by 40 percent in recent years.

These were not particularly sophisticated solutions, but entirely basic systems that now cost more than before.